- makeITcircular 2024 content launched – Part of Maker Faire Rome 2024Posted 2 weeks ago

- Application For Maker Faire Rome 2024: Deadline June 20thPosted 2 months ago

- Building a 3D Digital Clock with ArduinoPosted 7 months ago

- Creating a controller for Minecraft with realistic body movements using ArduinoPosted 7 months ago

- Snowflake with ArduinoPosted 8 months ago

- Holographic Christmas TreePosted 8 months ago

- Segstick: Build Your Own Self-Balancing Vehicle in Just 2 Days with ArduinoPosted 8 months ago

- ZSWatch: An Open-Source Smartwatch Project Based on the Zephyr Operating SystemPosted 9 months ago

- What is IoT and which devices to usePosted 9 months ago

- Maker Faire Rome Unveils Thrilling “Padel Smash Future” Pavilion for Sports EnthusiastsPosted 10 months ago

Open Source boats: the opportunity to build a foundation

Here at Open Electronics we are big fans of sailing.

A good old friend of mine recently participated to 2013 edition of Mini Transat, a solo sailing race that starts in late october in Northern France and ends up in South America, was in Guadalupe this year, actually Pointe-à-Pitre.

My friend’s race was definitely not a walk in the park: he first had some mechanical problems first nearby the Canarias, forcing him to stop there for a couple of days before getting back to the ocean, and eventually finished his race just hitting a container adrift, when few miles were still to be completed.

As many of you having a little knowledge about sailing can easily figure out, doing an atlantic solo race is not an adventure that you can setup in few weeks or months: it takes years to get prepared, train, accumulate miles, and eventually to get the pass to participate to such kind of challenges.

I know something about sailing

That’s why during the last few years, I learnt two or three things about sailing boats (and sailing in general: did you know I’ve got a natural talent for the rudder? At least that’s why my friend said).

Especially there’s one format that I know better, it’s that of the Minis. Mini is a particular form of sailing boat, it’s actually the smallest (non catamaran) boat that can go through the ocean: it’s just 6.5 meters long, you can barely sleep inside but it’s very cool as it’s a fully operating boat, just smaller.

This makes it the cheapest solution for sailors to get access to international challenges and makes if, year after year, one of the most active category of sailing races, due to lower access cost: this kind of boats vary in price between a couple of tens of thousands euros up to more than one hundred thousands for particularly advanced prototypes.

Production and Prototypes

Most of the times, when you need a mini 650 boat you go through two possible choices: buying a production boat of going for a prototype.

Prototypes are characterized by a lively second or third hand market, with good boats changing hands few times, before getting too old and scarcely competitive. Indeed prototypes are often better boat (from a challenge point of view): more advances, often faster, but they also are often built around the needs of a specific skipper.

The prototypes push the box rule to its limits and allow exotic building materials (carbon fiber) for the hull, deck, spars, bowsprit, rudders, etc, making them stronger, therefore allowing them to carry more sail area, with a deeper keel but an overall displacement lighter than a production Mini TransAt. These boats are one of the best way for sailors and architects to come up with innovations, before applying them on larger offshore racing boats.

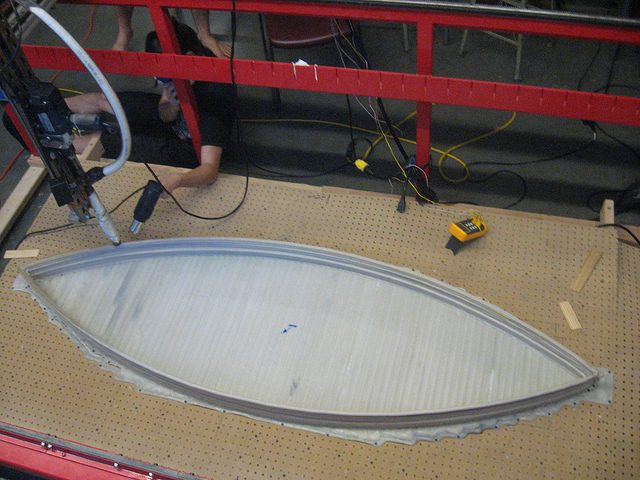

To build a prototype boat you’ve two actual choices: one is getting funded by sponsors, find an architect/boat designer (or design it by yourself) and get a boat builder to build it for you. The other one is still getting funded by sponsors, find an architect/boat designer (or design it by yourself) and then build the boat by yourself, as demostrated in this beautiful post narrating aDIY boat with incredible detail: http://joecoopersailing.com/building-a-mini-transat–6–50/ (will give you an idea of what does it mean).

So, while prototypes are boats where advanced solutions are implemented, they’re costly and for a boat more easy to buy, manage and use, eventually cheaper, you should probably look into production boats. By definition, production boats are boat that have been built at least 10 times:

Production Mini TransAt also fall into the box rule but do not allow exotic materials to build the boat, resulting in boats that are still carrying lots of sail area for its size and total displacement. However, spars must be made of aluminum and the structure, deck and hull are made of polyester resin. The result is still a boat that is fast, strong and able to cover thousands of miles. So, the first time a boat design comes up it belongs to prototypes: just after one producer or a licensee creates ten or more boats – and the materials and everything gets finalized – it can be considered a production boat and race in that sector, once you did at least 1000 miles and one of the boats qualified for the atlantic race.

The opportunity: building an open source foundation

As you can understand, this segment of the sailing boats market is still characterized by lots of different producers: everyone has it’s own brand and it’s own focus and it’s particularly appreciated for specific boat features. Yet, this market is targeting a huge user base, and a potentially growing one.

The sector is also characterized by a very distributed production network (all the boat builders that are scattered around the globe, ranging from the mediterranean area, to the US coasts, south america, and more) and by materials that are fairly easy to find and typically sourced locally. Despite it may be more complicated to actually produce the pieces from raw materials, the machines and skills needed to assemble boats are not that rare and complex.

The product itself – sailing boats, and specifically mini 650 boats – are characterized by pretty stringent features, size and weight requirements and therefore while each mini is different, each mini shares some basic configuration. These particular aspects of this market (distributed user base, distributed production network, low barriers to production, a pretty similar and limited product scope) make this sector particularly suitable to the creation of a foundation platform that could be easily declined into several specific needs, in a way that is similar – at some extent – to what we saw happening for RepRaps.

Approaches to create a modular and open source foundation platform, are emerging in several other industries these days, most of them being more complex and industrialized respect to sailing boats. You probably know already Project Ara – that has been featured several times here on Open Electronics – and you may have noticed that, in the last months, another thrilling project – that I recently joined – came under lights: OSVehicle, an open source, modular platform for Automotive solution.

If it’s thereby possible to hypothesize such a proposition for the automotive (despite this market is still getting mature I can assure we’re having a great interest from producers and users all over the world) this makes me think that applying this in the sailing industry would be much more easier and would make just the same amount of sense. Furthermore, another aspect makes this approach even more suitable for sailing. At OSVehicle, for example, you need fabrication hubs to produce kits that can be assembled locally by authorized dealers/assemblers.

Indeed, still digital fabrication is not mature enough to play a decisive role in this industry and, while things can change in the future at a pace that is hard to foresee, still the mechanical work needed to produce the actual kits of the open platform is machine intensive and complex and may require some scale pattern, to reduce the price: you may need molds to create parts, and this would end up adding costs if you’re not equipped to make at leat mid scale production.

Instead, building boats is typically still a much more artisanal work, and it’s heavily involving people’s knowhow more than machine advantage. In parallel, Digital Fabrication techniques are growing in quality and lowering in price (also thanks to open source) and this will eventually make access to such tools (Laser cutting, CNC, etc…) more easy. Also, Fablabs, Techshops and makerspaces are growing in number (according to Moore’s law as it seems) and these contexts may end up being new spaces, able to enable at least some part of the boat building process.

Having access to an Open Source model of saliling boats may also lead to the creation of small scale models, that would be super easy to build and may be tested by sailing hackers worldwide: that’s what, more or less, is doing Protei – the most advanced open source, sailing related project so fat – that is now building toys size exemplars of its sailing drones.

How would a project like this sustain?

There are several chances for a project like this to become sustainable. Crowdfunding may easily constitute a first funding strategy (maybe linking the creation of the boat to a long term mission, such as aiming to complete a Mini Transat campaign in few years) to step up the activities, fund the project and give birth to the core of the design activities and the community interaction platform.

On a longer term, this project may easily be incorporated in a Foundation living off donations and work contributions coming from sailing boat building companies around the world: that would be definitely similar to the way Linux foundation manages Linux.

Another pretty credible solution, could be similar to the one Arduino chose: the entity may issue a Trademark and try to get builders all over the world that want to produce such boats and brand them in a common way (virtually the “OS Sailing” or something completely unrelated) to sign some sort of paid agreement (a “developer program”) to be able to do this. This may really end up also in speeding the process to achieve access to the Production Mini TransAT Category as, despite being built by different producers, a number of 10 can be easily reached.

Obviously pretty anyone could make a business out of selling KITs and finished boats based on this design making the opportunity even more interesting.

Conclusions

In few word, I think a market for an Open Source / DIY Mini 650 Sailing boat it’s pretty mature: there’s the possibility to build an interesting crowdfunding campaign and get some big names in open source on board to such a campaign.

So if you’re interested in this project I suggest you to get in touch. I just put together a form for you to give feedback: if you’re a boat designer, a sailor, an engineer or a brand and you’re interested in supporting the project both with skills or financially, just reach out and we’ll keep you posted!

Photos courtesy of Washington Open Object Fabricators, Andrea Iacopini

Pingback: Maker | Pearltrees

Pingback: A bunch of Great Posts for you to re-read during the Summer | Open Electronics