- makeITcircular 2024 content launched – Part of Maker Faire Rome 2024Posted 2 weeks ago

- Application For Maker Faire Rome 2024: Deadline June 20thPosted 2 months ago

- Building a 3D Digital Clock with ArduinoPosted 7 months ago

- Creating a controller for Minecraft with realistic body movements using ArduinoPosted 7 months ago

- Snowflake with ArduinoPosted 8 months ago

- Holographic Christmas TreePosted 8 months ago

- Segstick: Build Your Own Self-Balancing Vehicle in Just 2 Days with ArduinoPosted 8 months ago

- ZSWatch: An Open-Source Smartwatch Project Based on the Zephyr Operating SystemPosted 9 months ago

- What is IoT and which devices to usePosted 9 months ago

- Maker Faire Rome Unveils Thrilling “Padel Smash Future” Pavilion for Sports EnthusiastsPosted 10 months ago

Maker Movement Turns Scientists into Tinkerers, says Scientific American

To do science, scientists need money—and usually a lot of it because specialized equipment and tools don’t come cheap. That means researchers often have to spend a significant amount of time pursuing funds from government agencies and private entities. But the era of open-source software and cheap hardware, including 3-D printers, is making it easier for them to quickly test innovative ideas and make their own research tools. These technologies are typically considered the dominion of “makers,” a word that evokes tinkerers and hobbyists, yet many scientists have begun to embrace the build-it-yourself ethos to advance their research in a variety of fields, including energy, transportation, neuroscience and consumer electronics.

With this incipit, the institutional Scientific American magazine empowers the trend according to which researchers in growing numbers are starting to enlist do-it-yourself 3-D printers, cheap electronics, sensors and more to advance their work.

In the hands of scientists, maker tools can help transform ideas into tangible objects, speed up research and stretch funding dollars, says Joan Horvath, co-founder of consulting firm Nonscriptum LLC, who organized the first maker symposium for scientists.

The joining of science and the maker movement is “not only a great thing but an inevitable thing,” says Conor Russomanno, co-founder of OpenBCI, a company that builds a low-cost brain-computer interface kit. The kit includes a 3-D printed electrode headset that fits on the head like a skullcap, a circuit board and open-source software that controls the technology. By opening up brain-wave research to DIYers and non-experts and encouraging an online data-sharing community, Russomanno hopes to accelerate neuroscience.

Last year, a group of U.S. Department of Energy scientists and engineers started using 3-D printing to make, quite literally, a gigantic change in wind turbine production. Making 30-plus-meter-long turbine blades costs millions of dollars and takes about a year, says Lonnie Love, a mechanical engineer at the DOE’s Oak Ridge National Laboratory in Tennessee. Using 3-D printing, Love and his colleagues now make them in weeks for tens of thousands of dollars. In addition to saving time and money, 3-D printing could make wind power generation more efficient. Wind patterns across a wind turbine farm change, Love says, “so ideally you want different blade shapes at different points to generate the most electricity.” Manufacturers today take a cookie-cutter approach to turbine blades because making them is costly and complex. With 3-D printed molds, they could fill wind farms with different cleverly designed turbines.

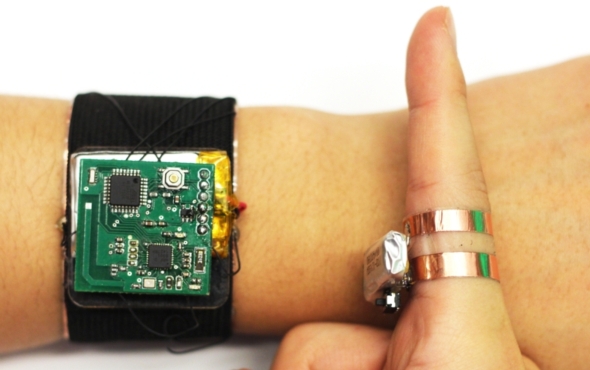

Beyond 3-D printing, scientists have also raided the maker toolkit for cheap sensors, open-source electronics and freely distributed software. For example, at Carnegie Mellon University, computer scientist Chris Harrison has invented a way to convert skin into a touchpad that might someday let smartwatch wearers navigate their tiny screens by swiping or tapping on their forearm. The SkinTrack system depends on an inexpensive radio frequency transmitter, an electronic sensor circuit built from a generic radiofrequency detector and transmitter chips and open-source Arduino microcontroller chips that the research team bought online.

Did this trend lowered the access threshold for wannabe scientist? Probably not, the scientific method needs more than open source and low cost tools to be “scientifically proof”, but for sure the Makers movements pushes further the “desire for scientific knowledge”, that is a real game changer for everyone nowadays.

Source: Maker Movement Turns Scientists into Tinkerers – Scientific American